Making Housing Affordable Again: Part 1

The Free Market is Not Causing the Affordability Crisis

The High Cost of Housing in Texas

Rev. Cyfers Ray, Jr. pastored a number of churches throughout his calling as a Baptist minister. When he retired in 1983, he and his wife Lizziebe purchased a house on the West side of Austin, Texas.

The house was a two-bedroom, one-bath bungalow that was often crowded with as many as six of the couple’s 12 children living there at times. But it had two major benefits: the family was close to other black friends and family in their Clarksville neighborhood and they were centrally located, just a mile from downtown Austin.

If Rev. Cyfers were to retire now, it is unlikely that scenario could repeat itself. The 958 square foot bungalow his family once lived in is now assessed at $989,957 by the Travis County Central Appraisal District. A 20% down payment on the house would be close to $198,000 and the monthly payment for the loan and property taxes would be about $6,300, likely far too much for the retired pastor. Not to mention a young family looking to buy their first or second home.

Austin may be the least affordable Texas city to live in, but it is not alone when it comes to rising housing costs. According to the Texas A&M Real Estate Center, the median price of a Texas house in September 2024 was $339,000, up from $180,000 ten years ago and from $127,378 in 2004.

A&M’s Texas Housing Affordability Index reflects these increasing prices. It computes a ratio of the median family income to the amount required to purchase a median priced home. The higher the index ratio, the more affordable housing is. “A ratio of 1.00 means that the median family income (MFI) is exactly sufficient to purchase the median-priced home.”

In 2011, when it debuted, the THAI was 2.06, meaning the median income provided just over double the amount needed to buy a median priced home. It peaked at 2.23 in the 4th quarter of 2012 and as recently as the 4th quarter of 2020 was 1.76. But it has plummeted in the last four years. The most recent THAI, in the 3rd quarter of 2024, is only 1.11. On average, a family with the median income in Texas can just afford to buy a medium-priced home.

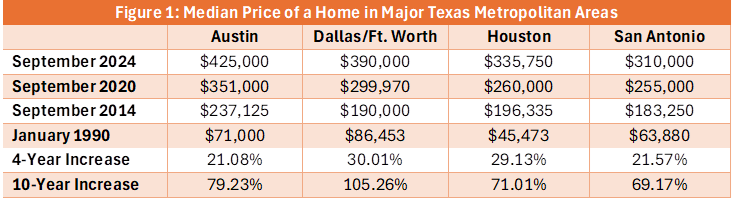

Figure 1 shows that the Austin metro area has the highest priced median home price in Texas, at $425,000. Dallas/Fort Worth is next, followed by Houston, then San Antonio. It also shows a significant increase in the median prices over the last 10 years, with the price in the Dallas/Fort Worth metro more than doubling, even though median family income increased by only about 45%. The increase in median family income in the other metro areas also lags significantly behind the increased housing costs.

The median price in Figure 1 is significantly lower in Houston and San Antonio than in Dallas/Fort Worth or Austin. That has not changed since the first year of the A&M data in 1990, though Austin has replaced Dallas as the metro with the highest median price and Houston and San Antonio have swapped places as the metro with the lowest median priced home.

A recent Harvard University study found that buyers in the Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, and Houston regions needed incomes between $100,000 and $150,000 to afford a median priced home. In San Antonio, the income needed was from $75,000 to $99,000.

The rise of housing prices outpacing income growth means that middle- and lower-income families have been the hardest hit. While the highest paying jobs are more often found in metro area centers, affordable housing is more often found in suburbs and rural areas. This often requires long commute times and affects the quality of life for many families, though the Covid lockdown-driven increase in working from home has softened this for some.

The Free Market is Not Driving the Housing Affordability Crisis

As discussed below, some people have called for intervention in the real estate market to solve the affordability crisis. But the market is not the problem. To help us understand this, let’s look at the primary participants in the housing market: developers, builders, home buyers, home sellers, renters, mortgage lenders, title insurance companies, and local, state, and federal governments.

We see in this list that there are basically two types of actors in the housing market, those who participate through voluntary transactions and those that impose regulations and mandates on the market participants. Thus, the primary price drivers in the housing market are supply and demand and external costs imposed on the participants by the government. Examining basic economic theory and the housing markets will help us understand that the market is not causing the affordability crisis.

The housing market is very complex with many moving parts. However, its basic premise is simple: buyers and sellers engage in voluntary transactions to trade ownership of housing at prices that benefit all participants.

One challenge Texas faces is its vibrant economy which continues to draw people from other states. The Texas Comptroller’s office reported the “Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington area led all U.S. metro areas in population growth and in net domestic migration between 2020 and 2023.” Unlike many other states, we must have significantly more housing each year to meet this growing need.

When developers respond to this by purchasing undeveloped land and beginning to put in the streets, sewage and water pipes, drainage, etc. that are needed to support residential housing, they do so because they expect they can sell the property to builders at a profit. Likewise, builders buy the property because they expect they can profit from building and then selling or leasing residential housing on the land. Those whose expectations match reality do indeed make a profit.

The main reality check for developers and builders is finding buyers who are in the market for purchasing or leasing housing at the prices being offered and believe they will be better off after they close their deal. The main reality check for buyers is finding housing that meets their size and location preferences within their budgets.

For instance, if the only potential buyers who tour a home in Highland Park are those who can only afford homes in Plano, both parties are going to be disappointed. The buyers had clearly set their expectations for the neighborhood they could afford too high, while the seller’s expectations of the market for buyers were also off kilter.

Yet in a free housing market unburdened by government intervention, the expectations and resources of buyers and sellers undergo this reality check in such a way that the expectations of bother parties can be satisfied. Buyers economize so they can afford a home that meets their expectations. Sellers compete on quality and price to satisfy the preferences of sellers. Both work within a framework of scarce resources and money which holds its value. Free market mechanisms, such as realtors, mortgage lenders, and insurers, develop to facilitate transactions between buyers and sellers. And because all of this must happen within the constraint of buyers and sellers making voluntary decisions limited by their own resources, there is no housing affordability crisis. Supply and demand reach equilibrium as all the changes and disruptions in the market work themselves out.

Complaints About the Free Market Do Not Hold Up

Some people claim that market factors are behind the affordability problem. Earlier this year, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott expressed concern on X about the activities of some investors. “I strongly support free markets,” he wrote. “But this corporate large-scale buying of residential homes seems to be distorting the market and making it harder for the average Texan to purchase a home. This must be added to the legislative agenda to protect Texas families.” Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar joined Abbott in his concerns about institutional investors in a report (p. 16) on housing affordability released by his office.

As reported in the Daily Texan, at the Texas Tribune Festival in September Austin City Council member Vanessa Fuentes supported Abbott’s call for government intervention to deal with housing. “One of the first policies that (Vice President Kamala Harris) talks about is a $25,000 down payment assistance program,” she said. “Even (Gov. Greg Abbott is) talking about taking on corporate landlords and institutional investors. This is an incredible moment where Democrats and Republicans see common ground, and it’s on housing.”

Yet, the numbers suggest institutional investors and other market factors are not the problem. Using data a Realtor investor report, Capital Economics Property Economist Thomas Ryan wrote, “With their small national market share, claims that large institutions inflate house prices seem exaggerated. In our view, lawmakers are looking for a new scapegoat to blame for unaffordable housing.”

Investors appear to follow the same pattern everyone else follows when it comes to home purchases. When investor purchasing slumped in the fourth quarter of 2023, Redfin reporter Lily Katz noted, “Investor home purchases have fallen as high interest rates, elevated home prices and a sluggish rental market have made investing less lucrative.”

The claim that “corporate large-scale buying [is] making it harder for the average Texan to purchase a home” is not supported by the data. On Fast Company, Lance Lamber reported, “The vast majority of investor purchases are made by small landlords who own fewer than 10 properties. In fact, according to John Burns Research and Consulting, institutional investors—operators owning at least 1,000 homes—accounted for just 0.4% of home purchases as recently as Q2 2023.”

This number is in alignment with research by Josh Kirby and John Burns who found that institutional investors made up around 2% of market activity during the housing crisis from 2007 to 2013. They further noted that long before institutional investors became involved in the housing market, small rental landlords “owned about 9% of all homes in America” and made up about 12% of all home transactions. So even though investors comprise “25% of residential real estate transactions today versus just 12% in 2002,” transactions by small investors far outnumber those by the large institutional investors.

Part 2: The Housing Affordability Crisis is a Creation of Government will be published tomorrow.

Don't forget the City & County Councils that are taking campaign donations from developers that are throwing up huge apt complexes on every square inch of our towns in North Texas. Denton leaders have completely changed the nature of the town from homey, safe, family town to crime ridden tenements.